incrementally losing my mind: some context

I have been playing Kittens Game for millennia at this point.[1] I have been working on this kitten civilization for just over seventy-two hours, but if I were to calculate how many real-world hours, I’ve had this game running I’d come up with a number higher than I’d like to admit.[2] Of course, I have the time to perform the math required to answer these questions because the game practically plays itself. Once I started automating the collection of resources, I stopped having to click “Gather Catnip.”

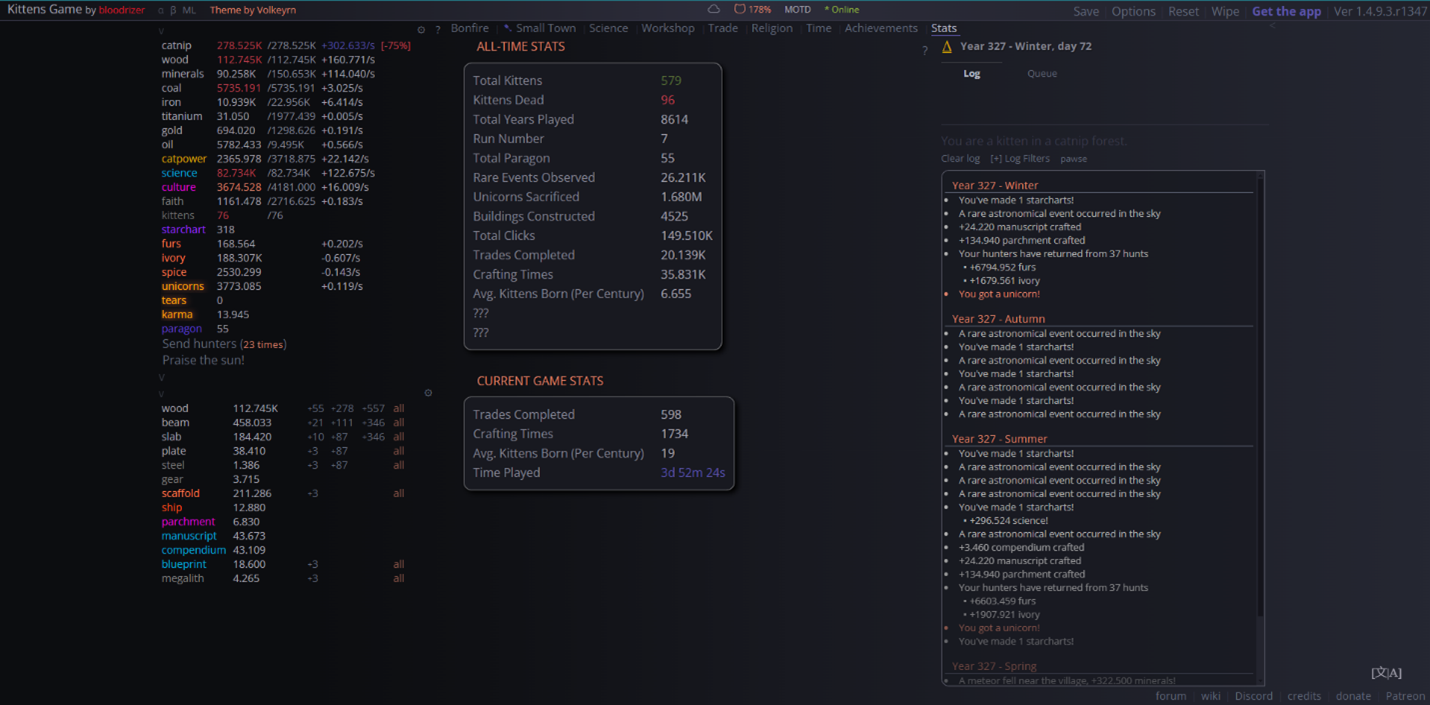

A screenshot of the Stats tab in Kittens Game.

Kittens Game is an incremental idle game. Incremental games are games where the complexity of the systems players interact with unfold over time. You might start with a few available actions, but by the midpoint of the game you could find yourself drowning in options. Idle games are games that you “play” by not touching them. These games are simulations, generally themed around resource production and management. Incremental idle games are games where the number of resources you are managing and collecting grows as you play; you discover new resources and systems as your existing resources and systems chug along. There’s something addictive about this genre of game. Seeing the numbers go up to ridiculous levels brings me genuine enjoyment. I think about my kittens when I close my eyes. What are they doing? How is their leader? Did I make the right choice investing in Monarchy?[3], [4] So much of my down time is checking the tab in my internet browser where Kittens Game is running, hoping that I’ve estimated my time correctly and that I have accumulated enough titanium to purchase my next upgrade. And for all this time I’ve spent “playing” this game,[5] I still am in what is considered the “early game.” I haven’t even unlocked Metaphysics yet.

Why do I like this game? Why do I obsess over similar games? I currently have Cookie Clicker[6] running in the background, I just finished The Barnacle Goose Experiment, I’ve previously played Crank and A Dark Room, and I have vague memories of Candy Box 2. There’s something to these games that scratches an itch in my brain. I’d like to know what it is.

[1] Eight millennia, to be specific. At the time of writing this first sentence, I have seen 8613 years go by.

[2] Roughly 478.5 hours. (Based on the table of values found here.)

[3] Yes, according to the guide by avocadho.

[4] This is, I believe, the only context where I can ever be quoted saying I opted for Monarchy.

[5] Again, I’ve spent the equivalent of twenty(ish) days, non-stop, on this game.

[6] Available for play in browser on the web and as a downloadable app on Steam.

thinking about comics :3

Recently, I’ve been trying to get into reading Marvel’s comics, but there are just so many series, issues, characters, and even universes for me to keep track of. Fortunately for me, there is an online project working on compiling reading guides: marvelguides.com. Even with this resource, navigating the past 80+ years of comic publication from Marvel is a massive undertaking. I’ve decided to start with the Silver Age (consisting of the comics published between 1961 and 1970-ish), which begins with Fantastic Four #1 (1961).

Why comics, dani? Why are you so interested in reading all the Marvel comics in order? The short answer: I have access to an archive of Marvel comics, I’m more familiar with the Marvel IPs, and I am specifically interested in long-form serialized comic narrative made by massive creative teams with various levels of cooperation. My first (and most cherished) comic series was Jeff Smith’s Bone. Reading Smith’s fantasy adventure and adoring the art style inspired me to make my own comics when I was in elementary and middle school. I had a bunch of comic strips, including a Pokémon rip-off called Eye (which had an associated rip-off card game), a Looney Tunes clone with an uninspired and apparently forgettable title, and a massive creative project titled NINJA!—a series of stick figure comics with a shared universe and lore. I hand-made the NINJA! comics, stapling sheets of paper together and drawing comics in pencil on these zines’ (hand-numbered) pages.

As I matured, my interest in comics changed. I explored (both reading and making) daily comic strips, one-panel comics, pun-filled joke comics, dramatic comics, “serious” comics, graphic novels, webcomics, webtoons, and self-aware comics. I experimented with art style, preferring a more minimalistic stick figure over cartoony or realistic character forms. And then… I started college and got busy and stopped drawing comics for a while. And then the world ended.

So here we are, living in the apocalypse, and here I am, teaching game design at university (lmao what the fuck how did that happen?) and wishing I could get back into making comics.

what is "queer"? (part one)

What is queer?

Introduction

Good morning gamers!

Just a heads up: in this series of essays I will be discussing the queer experience, which means that there will be content in here that deals with homophobia, slurs, anti-queer violence, and other hate crimes, as well as racism, transphobia, misogyny, ableism, and other forms of bigotry that impact members of the queer community. Queerness does not exist within a vacuum; intersectional thinking is essential for any discussion of identity.

I’ve been working with queer theory for a few years now, but I always find it a little bit difficult to figure out where to start when talking about queerness. It’s such a big topic with a myriad of interpretations and experiences; condensing it into a single paper, lecture, or book is an impossible task. Here, I’ve done my best to consolidate important contemporary discussions of queerness—and sexuality writ large—into a digestible piece of informational (read: educational) content.

My approach is built from my understanding of a concept called low theory, which I define as “a disruptive mode of theory that asks us to engage with it” (wright 10). Traditionally, academic texts are dense and indecipherable. It often feels like you need to take a course in reading these types of texts before you can begin to parse one—probably because that’s exactly what you need to do. Instead of making this traditionally academic, I’m going to aim for usefulness to a general audience. Fuck academia. This is queer theory and it’s meant for everyone.

Definitions

Queer, in this context can generally be understood as referring to an identity that fits under the LGBTQ+ umbrella. The word queer has a troubled history: it has been (and still is) used as a homophobic slur against members of the LGBTQ+ community, inspection of its etymology reveals an association with strangeness and otherness, and there is disagreement within the LGBTQ+ community about whether or not the word has been “reclaimed.” We will not be unpacking all of that today; that is a different job for a different essay. Instead, I want to focus on what systems and structures of power are hinted at using queer and an umbrella term for a set of identities.

In his 2017 MFA thesis paper, queer theorist and new media artist Matthew R.F. Balousek argues that queer is “most easily understood as the inverse of a set. Queers exists outside of heterosexuality and/or cisness as people of color exists outside of whiteness” (Balousek 2). This is an interesting place to start. It positions queer people as those excluded from the set of all people by the filter of having a cisgender and/or heterosexual identity. He also ties queerness to other systems of identity-formation—explicitly noting that people of color are non-white. Queerness cannot be separated from other identities because, in the words of Amanda Phillips, “[all] identities, after all, are fictions that organize us” (Phillips 8; Foucault). Calling identities fictions risks undermining the real and often harmful effects that they can have on us—especially when used as the justification for systems of classification that are then used to legitimize violence against members of a perceived identity group.

But queerness is more than an identity (or collection of non-normative identities regarding gender and orientation). Balousek defines queer as “the disruption, questioning, or opposition of normative structures, especially in regard to gender and orientation, and especially with the aid of

or an emphasis on relationality.” He argues that “[queer] as an ideology, then, is about the practice of this sense of the word in a broad sense” (Balousek 11). Queerness is a description of one’s identity and it is an active ideological position—a set of radical and disruptive politics and praxes. I understand that some people are uncomfortable with the violent history of the word queer, but language is malleable. Balousek wisely says that “in the mouth of a bigot, any word can become a slur” (8). It is more useful for this conversation to adopt Balousek’s proposed definition of queer instead of shying away from the term, sure, but it is also putting queer theory into practice to reclaim the word, to wrest it away from homophobic bigots who wield it against members of our communities.

“Straight,” “gay,” and “queer”

If queer means, among other things, the inverse of the set of heterosexuals and/or cisgender people, it creates an identity based on exclusion. To be queer is to be outside of what is considered “normal” with regards to gender and orientation. How can there be an understanding of what it means to be queer that is not based on such a binary logic? Do we have a name for identities that are “normative” other than the two obvious ones: normative gender and orientations and non- queer? One could argue that sure, there are terms for people who are not trans—we call them cis— and for people who are not gay—we call them straight. These are still constructed identities. To better understand how heterosexual and homosexual came to be, we must struggle to understand Foucault. I’m so sorry for this.

Foucault’s History of Sexuality

The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction is the first part of Foucault’s study of the development of the technology of sexuality. Originally published in 1976 in French as La volonté de savoir, or The Will to Knowledge, this book outlined what Foucault terms the “repressive hypothesis,” rebuts it, and presents a new version of the history of sexuality from the seventeenth century to the modern day (really, the mid-twentieth century, it’s been almost half a century since he wrote the book).

Foucault summarizes what he calls “the story,” his understanding of contemporary conversations about sexuality. He suggests that since the seventeenth century, we have seen more and more conversations about sex and sexuality, which discredits the notion that sex is repressed in our society; if sex is repressed, then why do we talk about it so much? Foucault rejects the story and its repressive hypothesis—that our society has been censoring and repressing sex and sexuality since the Victorian era—in favor of a more nuanced understanding of how and why sexuality is controlled. He is explicitly not arguing that there has been no censorship of sex or sexuality, he just means that the regulation of language and policing of sexuality fall into a category other than repression because of the growth in ways that we talked about it. He concludes that sexuality is not repressed in our society—that narrative is based on faulty logic; instead, sexuality is the focus of many discourses and conversations, and there has been an unprecedented growth and spread of the powers policing sexuality. The rest of Volume 1 is an analysis of the mechanisms of these powers, as well as the intention behind their deployment.

Foucault presents a list of features of the way power is presented in the West. Firstly, there’s what Foucault calls the negative relation—a description of how power can only be exercised over sexuality by limiting what is considered acceptable or allowed. In other words, power doesn’t say “yes” to any forms of sexuality, it either says “no” or has no comment on the matter. By overlooking quote unquote “valid” forms of sexuality—the conjugal couple engaging in procreative sex with the goal of reproduction—there is a judgement made about what counts as invalid—or aberrant, degenerate—forms of sexuality. This leads right into the second feature: the insistence of the rule; Foucault says that “sex is placed by power in a binary system: licit and illicit, permitted and forbidden” (Foucault 83). But beyond that, sex and sexuality must be understood in terms of the law (and discourse) and the language used to talk about legitimate and illegitimate forms of sex and sexuality is static; once a form of sex or sexuality is determined to be acceptable or unacceptable, that is the final say on the matter. This places the power in the hands of the group that defines valid sexuality. The third feature is the cycle of prohibition—the punishment of sex that is not suppressed. This feels like the idea behind the repressive hypothesis: Foucault says that power “constrains sex through a taboo that plays on the alternative between two nonexistences” (84). In other words, by prohibiting sex, either the non-normative forms of sexuality are suppressed or the people with non-normative sexualities are. Fourth in the list of features is the logic of censorship—Foucault identifies three forms of this feature: “affirming that such a thing is not permitted, preventing it from being said, denying that it exists” (84). This pairs with the third feature and again feels like the basis for the repressive hypothesis; I will remind us that Foucault does not argue that sex is not repressed at all, but that repression is not the primary way in which power is exerted over sexuality. Certainly, sexuality is rendered a taboo, the existence of non- normative sexualities is treated like a shameful secret. The fifth and final feature of how power is exerted over sexuality is the uniformity of the apparatus—there is no room for variation in how this power is exerted. There is the normative and the non-normative, there is the acceptable and the punishable.

Sexuality is entirely constructed. People do not naturally identify themselves as straight or gay, they just are or aren’t horny for people that share or don’t share their gender identity. Similarly, gender is a fabrication—a performance if you will. Nobody naturally identifies themselves as male or female because those words mean nothing outside of the context of a gendered society. Foucault’s whole point is that sexuality is used to control what is deemed appropriate and to justify the violence required to enforce that norm. This has some upsetting implications: namely that at some point, someone had to invent what heterosexuality meant.

Katz’s The Invention of Heterosexuality

I won’t spend too much time on this next text (in part because it is, at least for me, more intelligible than Foucault’s books) but I do want to highlight a couple points and encourage you to read Jonathan Katz’s book for yourself. In The Invention of Heterosexuality, Katz argues that “heterosexuality is not identical to the reproductive intercourse of the sexes; heterosexuality is not the same as sex distinctions and gender differences; heterosexuality does not equal the eroticism of women and men. Heterosexuality [...] signifies one particular historical arrangement of the sexes and their pleasures” (14). Katz shows that the first definition of heterosexual referred to a perversion of sexual appetites. To make a long story short, an American understanding of sexuality at the end of the nineteenth century raised procreative desire as the norm. Erotic desire and pleasure were simply not a part of the formulation of “normative sexuality.” As the twentieth century started, there was a new cultural understanding of what constituted acceptable forms of sexuality. Katz notes that the “making of the middle class and the invention of heterosexuality went hand in hand” (41). Heterosexuality as a norm is, therefore, tied to the development and enforcement of sexuality, class, race, and gender divisions.

queer theory

How does queerness connect to theory? And what even is theory, anyways? Why does it matter? When I talk about theory, I’m really talking about a mode of critical theory, a branch of philosophy that is kind of obsessed with revealing and challenging systems and structures of power. Queer theory uses queerness as a lens through which an analysis is made; a theorist can attempt to understand a social system in relation to queerness and identity and propose ways to challenge the status quo with the goal of basically fixing a broken system (usually through some rejection of the status quo and a restructuring of things rather than the neoliberal ideal of working within a system to change it).

Queer theorists challenge the idea that cisgender and heterosexual are the normal, baseline identities. We analyze the power structures built to enforce norms and challenge them, offering new ways of understanding gender and sexuality outside the limited view of a hetero-/homo- binary. Here, I’ve done my best to explain what queerness is and how our understanding of sexuality has been constructed. In the future, I’ll look closely at the work of some important queer theorists and explain some big concepts in queer theory.

Good night, gamers.

Works Cited

Balousek, Matthew R.F. "Opening the Horse: An approach to queer game design." Santa Cruz, June 2017.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Vintage, 1990.

Katz, Jonathan. The Invention of Heteropsexuality. University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Phillips, Amanda. Gamer Trouble: Feminist Confrontations in Digital Culture. New York University Press, 2020.

wright, dani. "blood play: a queer gothic approach to game design." Santa Cruz, June 2022.

what the fuck are poetics?

what the fuck are poetics?

What follows is adapted from my MFA thesis paper; here, I explore in further detail a part of my research interest: this nebulous thing called poetics. I hated this topic, in part because nobody had a good definition of what the fuck poetics meant. There were plenty of essays and books that talked about a poetics of [x], but they were treatises concerned with whatever the hell [x] was and assumed we were all on the same page about what poetics was supposed to mean. I was frustrated, yeah, but more than that, I was curious. This was a thing I wanted—no, needed to know. And, like most of the worst parts of my academic experience, I learned that it was all the fault of some Ancient Greek asshole.

what does “poetics” mean?

Aristotle wrote this book called Poetics in the mid-fourth century BCE. Well, wrote is a generous description; most of what we currently consider his “writings” are, according to Malcolm Heath, really surviving scraps of notes he made on his lectures;

“The process by which they took their present form is unclear; in some cases there are signs of editorial activity (either by Aristotle himself or by later hand); so different versions may have been spliced together, and what is presented as a single continuous text may in fact juxtapose different stages in the development of Aristotle’s thinking” (Introduction vii).

In Poetics, Aristotle explains what a poem is, what types of poetry exist, and how poets create poetry. He spends most of his time discussing the poetic form of the tragedy, but the discussion serves as a model for identifying and describing other poetic genres. All types of poetry are, to Aristotle, “imitations. They can be differentiated from each other in three respects: in respect of their different media of imitation, or different objects, or a different mode…” (Poetics 3). Here, he is straightforward: poetry refers to art where “the medium of imitation is rhythm, language, and melody…employed either separately or in combination” (Poetics 3–4). He goes on to note that “the art which uses language unaccompanied, either in prose or in verse…, remains without a name…” (Poetics 4). So, poetry refers to art that uses language and can be heard, performed, or read. This is incredibly vague and unhelpful; I find it difficult to identify a piece of art that does not fit into this definition of “poetry,” but maybe that’s the point—maybe anything can be poetry.

Great, I’ve got poetry down. Kind of. Now my question is: what the fuck are poetics? In her 2020 book, Poetic Operations: Trans of Color Art in Digital Media, micha cárdenas provides a definition that has been essential to my understanding of what poetics are: “Poetics should be understood here as the meeting of intention and expression; all the ways that matter is used to communicate, where matter includes concepts expressed as words, sound, or gesture” (29). This is an incredibly helpful starting point for a discussion of poetics—it establishes that they are the intentional use of forms of expression, with the unstated goal of expressing something. To expand upon this, I turn to The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, which states that “poetics may be used as a label for any formal or informal survey of the structures, devices, and norms that enable a discourse, genre, or cultural system to produce particular effects” (1059). In other words, poetics describe the tools and strategies that—and here, poet can refer to anyone creating media that might be considered poetry, whether or not it is verse-poetry—poets use to elicit some effect, or emotional response, from an audience.

what does “a poetics of [x]” mean?

I approach this from the perspective of an artist; this is my understanding of what is meant when authors, critics, and theorists write about a poetics of [x]: there is little explanation of what the fuck a poetics is and, frankly, too much explication of that the hell [x] is. Critics—especially poetic critics—approach this from the opposite direction; they use poetics to identify what genre or subcategory art fits into. If a piece of media appears to engage with a poetics of [x], then [x] is a useful lens to analyze and critique the art through—the media fits into the genre of [x] and can be treated and evaluated as such. But to me, this understanding of poetics feels too nebulous, too hard to pin down.

Fortunately, my understanding of poetics—aided by both cárdenas and The Princeton Encyclopedia and hampered by Aristotle—fits into an existing framework I am familiar with—the MDA framework for game design. In their 2004 paper, Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubeck identify elements that make up a game’s played experience: the mechanics—a game’s rules and parts, the dynamics—a game’s systems and emergent behaviors, and the aesthetics—the player experience. Hunicke et al. also describe two perspectives on the game:

From the designer’s perspective, the mechanics give rise to dynamic system behavior, which in turn leads to particular aesthetic experiences. From the player’s perspective, aesthetics set the tone, which is born out in observable dynamics and eventually, operable mechanics.

(“MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research” 2)

This describes how a game designer—a game poet, if you will—can design the systems of a game in order to evoke an emotional response from the player. Games are poems, their designers are poets, and these poets use many types of poetics, but especially a poetics of play, to make their audience feel something.

So when people talk about a poetics of [x], what they mean is that by using [x] as a design guide, they can create media that elicits a specific emotional and aesthetic response—one that is in line with the emotional and aesthetic values associated with [x] as a genre.

how are poetics useful (if at all)?

This is where I’m really starting to deviate from the trail I followed in my thesis paper. I had a rough understanding of what poetics means, but I was more interested in exploring the queer gothic genre I was trying to work within. But here, outside the context of a graduate program, I can dive deeper into this weird topic and as the tough questions, like who the fuck cares?

Poetics are a tool for artists and critics to use to facilitate either the creation or analysis of art. But let me problematize that word, art, for a second.

what is art?

What are the boxes something needs to check to qualify as “art”? I’m going to answer these questions with another question: why the fuck does it matter?

Art is, in my understanding, a piece of media that was made or designed. It can be made in any medium (which is why I will use the words media and art interchangeably) and there are no other qualifications. So long as someone can argue that a piece of media is art, I will agree with them. This does not mean I fully and wholeheartedly endorse all pieces of art. What’s that thing Oscar Wilde wrote? “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all” (The Picture of Dorian Gray 3). I’d like to challenge that. There is no such thing as a piece of art that is, by itself, either moral or immoral. However, a piece of media—regardless of the technical skill that went into creating it—can be (and often is) a vessel for the beliefs of its designer(s) and, as such, can be considered malicious, hopeful, or, yes, even immoral. Some books are born bad and some books are twisted by their readers. Art, or media, is thought given form; some ideologies are fundamentally incompatible with a cultural understanding of what is good and right.

This is all to say that The Picture of Dorian Gray is a good book with serious flaws and [generic magic school YA series written by a TERF] are bad books with serious flaws. But just because, say, Harry Potter sucks and so does its author, that doesn’t mean it isn’t still art. It is; it’s just shitty art that erroneously believes it’s both good and moral.

Anyways, back to the essay.

back to the essay

Poetics: what are they? As I was saying, they are a tool for both artists and critics.

For artists, they help guide the process of working within a medium to evoke an emotional or aesthetic response in an audience that is tied to, you know, whatever the poetics are of. Using a poetics of space, as explicated by Gaston Bachelard, an artist can play with the affordances of both three-dimensional space and relationality between objects as well as the affordances of the materials they are using to construct their work to effectively convey or evoke a set of ideas or beliefs or feelings in the (potential) audience.

For critics, poetics are a framework or a lens through which they can interpret a piece of media. Using the same poetics of space, a critic or analyst can interpret how, say, a piece of architecture engages with the affordances of the medium of concrete and metal and such to convey or evoke a set of ideas or beliefs or feelings in the people who are moving through the (negative) space of the piece of art that is the object of construction—be it a building or a sculpture or a gazebo or what have you.

So are poetics useful? Yes, but their usefulness is determined by a few factors: primarily how well a poetics of [x] has been explained, how well a poetics of [x] has been interpreted, and how well a piece of media interacts with [x]. The explanation of a specific poetics by a theorist, their interpretation by an artist, and the interaction between them and the specific piece add up to the overall usefulness of poetics as a lens for creation and interpretation of a piece of media.

works cited

Aristotle, and Malcolm Heath. Poetics. Penguin, 1996.

cárdenas, micha. Poetic Operations: Trans of Color Art in Digital Media. Duke University Press, 2022.

Hunicke, Robin, LeBlanc, Marc, and Zubek, Robert. “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.” 2004.

Preminger, Alex, et al. Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Wilde, Oscar, et al. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Penguin Books, 2020.

gothic genre/mode (part one)

On Christmas Eve in 1764 Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto which, by most accounts, was the first Gothic novel. Otranto is the story of how Manfred, an Italian nobleman, decides to attempt to divorce his wife and marry his almost-daughter-in-law because his son died on his own wedding day (before the ceremony) and that was…the best course of action in Manfred’s mind? It’s actually a much more complicated narrative that involves supernatural omens, a curse on a family, a rightful heir, a giant helmet, and a chase scene through a ruined castle, but it is also about Manfred trying to marry his son’s fiancée. The Castle of Otranto certainly established Gothic conventions and tropes— “sexualized power dynamics, supernatural elements, and terrorized and vulnerable women” (Westengard 1–2)—that can be found in contemporary media (especially within the horror genre). But aside from being a specific historical literary genre, what does Gothic mean? And what is the difference between Gothic and gothic?

Gothic culture(s)

Gothic has meant many different things over the past seventeen hundred years (give or take). To uncover the history of the term, I turned to Nick Groom’s The Gothic: A Very Short Introduction. Gothic first referred to “barbarian tribes” from Germania, the region north of the Roman Empire, who were called the Visigoths (Western Goths) and the Ostrogoths (Eastern Goths). The Visigoths were pushed out of Eastern European territory by the Huns and, in 376 CE, were allowed to cross the Danube and enter Roman territory (The Gothic 4). The Romans were super chill about the whole thing, and everyone lived happily ever after.

Wait, that isn’t right.

The Romans and the Goths fought in bloody wars. In 410 CE Rome was sacked and in 475 CE, the Visigoths declared their independence from Rome—which collapsed the year later (The Gothic 6). The Ostrogoths, meanwhile, were split into two main groups: those under Hunnic control and those under Roman-Byzantine control.

Following the fall of Rome, Gothic culture developed an origin story that justified both the Goths’ status as the successors to Rome and a unification of Gothic cultures. Basically, the Goths were Catholic now, baby! Groom argues that “the Goths had not only sacked Rome and overrun the old Empire, they had effectively sounded the death-knell of the classical pagan world” (The Gothic 12). This association between Gothic and Catholic would last until the Renaissance, when Gothic started to refer to medieval architecture and culture (which was not meant as a compliment). Renaissance Europeans were Big Fans™ of Greek and Roman culture, which they believed were destroyed by the Goths who introduced “bad art and architecture” that was decadent—full of decorations like gargoyles and buttresses.

But let’s be honest, Gothic architecture fucks. It is generally split into four major periods: Norman Gothic (which spanned from 1066–1180 ish CE), Early English Gothic (which lasted from about 1180–1275 CE), Decorated Gothic (which is dated from 1275–1375 ish CE), and Perpendicular Gothic (which lasted from about 1375–1525 ish CE). Many Gothic buildings were churches, especially those in England, which used their impressive construction as a rhetorical connection to the divine and the infinite. “If this is a house of God,” they seemed to say, “it might as well look the part!” But these religious buildings weren’t all bright and cheery; Groom argues that there was “a culture of death that was centered on churches” (The Gothic 23). The Gothic cathedral was a massive memento mori—a reminder of death’s inevitability.

Europe had a little bit of a moment with the Catholic Church: The Reformation. Protestants were now a thing and they hated Catholics and Catholics hated them right back. They loathed each other so much that they were willing to go to war for decades with each other over ideological differences. The Protestants didn’t like that the Catholic Church was corrupt, and the Catholics didn’t like that being pointed out. And the Catholics did have their own Counter-Reformation where they tried to fix some of the shit that they got called out on. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

England had a complicated take on the Catholic Church. They were proud to be Catholic and not Protestant, but then Henry VIII wanted a few too many divorces and the pope was hesitant to annul another marriage. So, like a mature world leader, Henry VIII threw a tantrum and made his own Catholic Church knock-off: the Anglican Church. So, England was Protestant. And English people are known for being calm and level-headed.

Wait, I read that wrong.

The English went fucking ballistic, killing each other and razing their own land in the one-two punch of the English Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Henry VIII and his son weren’t Catholic and then Queen Mary was, but she was executed and then the English were Anglican again. Groom says that after the violence of the English Reformation(s), “English identity was rooted in a violence on a terrifying scale” (The Gothic 24). Which isn’t true because the English had been and would continue to be kind of oppressive dickheads who committed genocides against pretty much everyone they could. But it is true that in the wake of the mass destruction and violence, the English landscape was littered with half-alive ruins of religious buildings (made primarily in the Gothic styles) that served as a painful reminder of that time they turned their brand of violence inward.

English culture didn’t really know how to grapple with the collective trauma of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation (which should not be confused with the other Reformation and Counter-Reformation, which happened in a magical place called “not in England”). Kind of like the United States of America in the wake of the September 11thattacks, English cultural production fixated on the trauma of the iconoclasm primarily through things like ballads and the Revenge Tragedy. Both modes of cultural production seemed to highlight violence—often sexual in nature—and the supernatural; both were dark in tone and obsessed with death and ruin. English art and culture could not stop thinking about how bad shit got. These themes would percolate for a little while and eventually make their way into Gothic literature, but before the genre could enter the picture, there was a little bit of political groundwork that needed to be done.

The Romans weren’t really all that cool to the English anymore. I mean, right off the bat, Rome was where the Catholic Church started, and Catholicism was No Longer Cool. And their whole absolutist monarchy system wasn’t vibing with the republican sentiments of a pro-parliament Britain. Enter the Whigs.

The Whigs were a British political party whose official stance was “fuck the monarchy” …kind of? They opposed the Tories, who ended up becoming the modern-day Conservative Party in the UK, but everyone still calls the Conservative Party the Tories. The Whigs were in favor of a constitutional monarchy. Oh, and the first Prime Minister of the UK was a Whig politician named Robert Walpole. Horace Walpole’s father. We’ll come back to that. The Whigs started associating themselves with Gothic culture, which was seen as valuing personal freedom in opposition to absolutism and tyrannical leaders. Gothic sentimentality was politically progressive; no longer was England under the control of the imperial Roman authority or the absolute power of the monarchy. The Whigs had established the office of Prime Minister and opposed the domination of the Catholic Church. Gothic was synonymous with political progress.

Enter Horace Walpole.

Gothic literature

The Castle of Otranto was a vessel for Whiggish sentiment: its plot is “based on fraud and inheritance, expressing perhaps a fear of the legitimacy of English Teutonism and the Gothic heritage” (The Gothic 71). It was the establishment of a new genre of art, a new mode of cultural production that featured decadence, ornamentalism, supernaturalism, and an aesthetic of death and decay. It was a “metaphor for the less tangible anxieties and traumas of the human condition” (The Gothic 72). In his introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Castle of Otranto, Nick Groom suggests that Walpole was not so much establishing a new genre, but rather that Otranto represented “the climax of eighteenth-century discussion and debate about the Goths and ‘Gothick’” (“Introduction” ix). I see where Groom is coming from, but I also want to highlight that Walpole was explicitly outlining a new mode of artistic expression. Yes, it built upon the eighteenth-century discourse, but it also developed a whole set of practices that have fundamentally changed how we write today. Gothic techniques have spread to influence many genres of writing, ranging from literary fiction to philosophy.

a summary of The Castle of Otranto

The Castle of Otranto is about a lot of things, but it’s also short as novels go—both of my copies are just over one hundred pages in length. If you haven’t read it, I encourage you to do so; the whole text is available online for free[1] and the text itself isn’t too dense. There are content warnings, which I’ll provide here.[2] But if you haven’t read it, I’ll quickly summarize what happens. As a note, all page numbers I use for my citations are from the Penguin Classics edition of The Castle of Otranto unless otherwise noted (as I have with excerpts from Nick Groom’s introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition).

Before the narrative starts, the preface to the first edition of the novel gives some context for what the fuck The Castle of Otranto is. The “translator,” William Marshall, says that he found this history in “the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England” (Walpole 5). Marshall also notes that the manuscript was printed “in the black letter,” which means a Gothic-style font (Walpole 5). He implies that the work is likely an embellishment of an actual history, noting that the names used are fictitious and that the original author’s writing “can only be laid out before the public at present as a matter of entertainment,” but goes on to state that he “cannot but believe that the ground-work of the story is founded on the truth” (Walpole 6, 7). And then the story started. But after the success of the first edition of this novel, Walpole revealed himself as the author and the work as pure fiction. When a second edition was printed, Walpole included a second preface that explained a little bit more about his motivations: he wanted to “blend the two types of romance, the ancient and the modern” (Otranto 9).

Manfred is the prince of Otranto, and he has two children, his daughter, the “most beautiful virgin,” Matilda—whom he dislikes—and his son, the “sickly” Conrad—whom he adores (Walpole 17). It is Conrad’s wedding day and Isabella, his bride and the daughter of a marquis, has been at Otranto for a while, waiting for Conrad to be healthy enough to make it through the ceremony.

Oh, also there is a weird prophecy that implies that Manfred is not the rightful lord of Otranto.

Anyways, Conrad is late to his wedding ceremony and Manfred is impatient. He sends someone to look for the boy and they come back terrified and raving about a helmet, which makes no sense to anyone until most of the wedding party go out of the chapel and find Conrad’s body crushed underneath a massive helmet. Manfred is super normal about seeing his beloved son’s mangled corpse and has no emotional reaction, instead giving orders for Isabella to be taken care of. This is kind of silly because Isabella was not a big fan of Conrad or Manfred, so she’s kind of feeling relieved to not have to go through with this marriage. Later in the evening, Manfred goes to visit Isabella and basically tells her that Conrad was a loser, she deserves a real man…perhaps one named Manfred. Which is gross and borderline incestuous? Manfred isn’t technically her father-in-law because Conrad died before the marriage, but she was still viewing Manfred as her parent (in a loose sense). When Isabella points out that Manfred is married to Hippolita, he declares that he is divorced from her because she couldn’t give him an heir. Manfred grabs at Isabella but she runs like hell, managing to escape into the castle’s subterranean passages.

While she is stumbling through the dark labyrinth Isabella bumps into Theodore, a peasant who identified the deadly helmet as one from the statue of a former prince of Otranto: Alfonso. When Theodore pointed this out to Manfred, the prince lost his temper, called Theodore a necromancer, and had him trapped inside the massive helm. But Manfred’s plan didn’t go smoothly; the helmet was so heavy that it punched a hole in the street that dropped Theodore in the passageway. Theodore helps Isabella escape the castle’s grounds and she runs to St. Nicholas’ church nearby. Father Jerome, the holy man in charge of St. Nicholas’, makes his way to Manfred’s castle and asks for an audience with him. Jerome says that Isabella is going to stay under his watch until her father comes to collect her, which displeases Manfred. “I am her parent […] and demand her,” he cries (Walpole 44–45). Manfred is acknowledging that he is, in all but the legal sense, acting as Isabella’s father right now. But he wants to marry her and argued that he would “value her beauties” and “may expect a numerous offspring” (Walpole 23–24). His claim as Isabella’s father and his proposal of marriage to her are discordant and emblematic of the sexualized power dynamics that Gothic literature would come to center.

Manfred recaptures Theodore and is ready to kill him when Jerome recognizes Theodore as his bastard son; Manfred stays his hand. It is revealed that Jerome and Theodore are descended from the noble house of Falconara, which makes Theodore a threat to Manfred’s claim to the throne, per the weird prophecy. Theodore is of noble blood. Father Jerome asks Manfred, “what is blood! what is nobility!” The priest goes on to assert, “We are all reptiles, miserable, sinful creatures. It is piety alone that can distinguish us from the dust whence we sprung, and whither we must return” (Walpole 52). While he is technically spared, Theodore is locked away in a tower.

Later, some knights of the lord Frederic, the marquis of Vicenza (who has a claim to the throne and is also Isabella’s father), arrives at Otranto. Frederic was out fighting in the Holy Land (read: committing genocide in the Crusade) when Manfred “bribed the guardians of the lady Isabella to deliver her up to him as a bride for his son Conrad; by which alliance he had purposed to unite the claims of the two houses” (Walpole 56). In other words, the whole engagement was something Manfred orchestrated without the consent of anyone involved. While Manfred is talking to Frederic and his men, Matilda (Manfred’s daughter) helps spring Theodore out of his tower prison. Back with Manfred and Frederic, things are getting wild; everyone is scrambling to find Isabella before the others can. Down in the passageways, a knight bumps into an armor-clad Theodore who stabs the shit out of him in defense of Isabella before he realizes that, oops, it was Frederic.

Everyone makes it back to the surface and, for some fucking reason, Frederic falls in love with Matilda and is like, “Hey, Manfred. I know we’re having a horrible time trying to find my daughter and marry her off to secure our claim to the throne but how about this: you marry my daughter and I marry yours? It sounds like a fair trade.” I guess Manfred finds this amenable but he thinks that Theodore and Isabella are hooking up in the chapel so he grabs a knife and runs down there to stop it.

Now, here’s the thing about Manfred: he’s a stab first, ask questions later kind of guy. He barges into the chapel, sees Theodore and some girl, and plunges the dagger into this poor girl’s bosom. Matilda cries out, “Ah me, I am slain!” and collapses (Walpole 95). Manfred realizes that he’s killed his daughter and lost his son; his line is effectively ended. Well, Matilda isn’t quite dead yet but she’s not going to survive. As everyone is making their way to say goodbye to Matilda, who is taken to her chambers, there’s a big clap of thunder and a ghost wearing massive armor—specifically the ghost of Alfonso, the former prince of Otranto who’s statue’s helmet crushed Conrad—proclaims that Theodore is the new and rightful prince of Otranto. Also this massive ghost destroys the walls of the castle before ascending into the clouds and vanishing. The next day, Manfred abdicates his claim to the throne of the principality before he and his wife take “the habit of religion in the neighboring convents” (Walpole 100). Theodore ends up marrying Isabella even though he’s all broken up about his dead almost girlfriend because “he was persuaded he could know no happiness but in the society of one with whom he could forever indulge the melancholy that had taken possession of his soul” (Walpole 101).

So that’s the story ofThe Castle of Otranto. Manfred tries to marry his daughter in law and ends up securing the end of his bloodline. It’s largely a story about questioning the legitimacy of the claims of nobility, highlighting the violence needed to maintain one’s family legacy, and building a cultural mode of expression out of the aesthetic of ruin that helped shape a post-iconoclasm English identity.

bibliography

Groom, Nick. The Gothic: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Reeve, Clara, and James Trainer. Old English Baron. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Walpole, Horace, and Michael Gamer. “Introduction.” The Castle of Otranto. Penguin Books, 2001.

Walpole, Horace, and Michael Gamer. The Castle of Otranto. Penguin Books, 2001.

Walpole, Horace, and Nick Groom. “Introduction.” The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014.

Walpole, Horace, and Nick Groom. The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Westengard, Laura.Gothic Queer Culture: Marginalized Communities and the Ghosts of Insidious Trauma. University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

[1] https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/696/pg696-images.html

[2] misogyny, sexism, sexual harassment, death, child death, sexual assault, adult/minor relationship, infertility, incest

the haunted house as a site of queer trauma

While I was working on my MFA thesis paper, I read a lot of queer theory. I am by no means an expert, but I do know a bit more than average. Queer theory is a branch of critical theory—itself a branch of philosophical thinking that critiques and challenges systems and structures of power (e.g. race, white supremacy, class, gender, patriarchy, etc.)—that focuses its analytic lens on systems and structures of normativity with a specific emphasis on those concerned with gender, sexuality, and identity. In this way, queer becomes more than an orientation or identity; queer is a radical, disruptive ideology. Queer is different than gay because gay describes sexual orientation, not a set of political beliefs and actions. Because queer theory is a lens through which we can analyze and interact with media, we can blend it with other analytical and philosophical approaches. This is exactly what Sara Ahmed does in her 2006 book, Queer Phenomenology.

You don’t have to understand what phenomenology is (a philosophical approach to understanding something by observing how it exists), nor do you have to read Ahmed’s book (though I implore you to because it is wonderful and digestible). All you need to know is the following:

I was working on a thesis paper about the inherent queerness of the gothic genre by focusing on the vampire as a tragic queer figure;

I was in a two-year Masters of Fine Arts program;

I could not stop thinking about how vampires are queer;

Ahmed is a brilliant queer theorist and Queer Phenomenology was an integral part of my transformation from “just some game designer” to “just some game designer and theorist;”

The quote I am about to discuss almost shattered my fixation on twilight and its vampires (who are so fucking gay don’t even get me started);

And finally, I am dead set on getting my PhD so that I can write my dissertation about this next fixation of mine, which was entirely brought about by me reading (and rereading) this quote.

Are you ready? Here we go. “Now in living a queer life,” Ahmed opens, “the act of going home, or going back to the place where I was brought up, has a certain disorienting effect. As I discuss in chapter 2, ‘the family home’ seems so full of traces of heterosexual intimacy that it is hard to take up my place without feeling those traces as points of pressure” (Ahmed 11–12).

Fuck.

That quote—those two sentences—irreversibly changed my entire academic career. And I could not be more grateful.

Let’s unpack this, shall we?

“Living a queer life” means more than just being gay, as I previously argued. It means being radical and disruptive. It means challenging social and societal norms surrounding gender expression, sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexuality. Ahmed says that by living this way, by embodying queer politics, the feeling at home, at the place where we grew up, is fundamentally changed. It is disorienting. Queer people can—and often do—feel like they cannot be themselves at home because it is “so full of traces of heterosexual intimacy.” These traces are reminders that queerness has no place in the “family home.” The entire structure of the family unit is built to generate, affirm, and enforce heteronormativity. It is disorienting, discombobulating to come from a queer life and a queer home and return to the “family home,” the place where you were raised because you are aware that there is no room for you, for your politics, or for your identity. Taking up one’s space in the “family home” becomes a struggle and you are constantly feeling the pressure of bumping up against the systems built to invalidate your identity and experiences. Ahmed’s use of the word “traces” was what really got to me. It reminded me of ghosts, and that got me thinking about one of the very first books I read as part of my thesis research: Laura Westengard’s Gothic Queer Culture.

In their book, Westengard argues that the gothic and queerness are inextricably linked. She specifically looks at how trauma operates in gothic media, how queer media uses gothic motifs to express a queer trauma, and how the gothic mode relies of queer techniques of meaning making. They assert that “[…]there is something about gothicism that resonates with the experience of queer precarity in a system built to maintain normativity, a connection between existing in a world built to deny and devalue queer expression and the creation of gothic content. In other words, if something is both queer and gothic, look under the surface to disinter the insidious trauma buried there” (Westengard 2). So here’s the thing about gothic media: trauma is often represented through the haunting, the return of the repressed. And ghosts—the monsters that haunt—are traces of trauma left behind. When you are living a queer life and you return to the “family home,” you are haunted by the traces—ghosts—of heterosexual intimacy because they serve as a reminder of the accrued “trauma of being queer in a system built to invalidate and destroy anyone who strays from the norm” (Westengard 3).

This is the premise of my current line of academic inquiry: I read the haunted house as a site of queer trauma. I will outline a framework for understanding the House as a representation of family legacy, of the bloodline, of generational logics that builds upon existing queer theory about the Child as a representation for the potential of new generations created via heterosexual coupling and reproduction. The House (I get to give it a capital ‘H’ because Lee Edelman gave “the Child” a capital ‘C’) is the structure that the Child exists within; while the Child is all about futurity, the House is rooted in legacy. The House is the enforced heteronormative family unit that transfers power from one generation to the next. Queer people are not welcome in the House because they threaten the continuation of the legacy; queerness threatens to destroy the foundations of the House. And so the House is haunted for us: haunted by the insidious, accrued trauma Westengard focuses on as well as the traumatic moments that we live in terror of. I will propose a new way of organizing the family that queers the notion of the House and queers the way in which it is haunted.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology. Duke UP. 2006.

Westengard, Laura. Gothic Queer Culture. U of Nebraska P. 2019.

oh gods it's been a whole year already

its september again??? when did that happen? i guess i'm finished with my first year at DANM? that feels weird. (granted, i am missing a 3–6 month chunk of memory due to medical stuff, but that's a can of worms i don't want to open right now.)

so what have i been up to? (that's both a rhetorical question for a smooth segue and a genuine question because i honestly don't know.) first of all, i put together my committee! i mean that's like, required and all. but i did it. this summer i've been working on my thesis proposal and the first draft of my paper so that i can get my Queer and Gothic design principles solidified before i start making a game guided by them. outside of thesis work, i finished ta'ing for the UC Santa Cruz game design capstone course and the COSMOS summer program for high schoolers and learned two things. 1) holy shit my students are so incredibly talented and capable and 2) hey, i kinda like being on the teaching side of things. i'll just keep that in the back of my mind for a while.

right now i'm working on finishing up some of the bigger readings i assigned myself. this summer, i knocked out:

In a Queer Time and Place by Jack Halberstam

Queer Phenomenology by Sara Ahmed

Poetics by Aristotle

The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez

The Vampire Diaries Volume I: The Awakening by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries Volume II: The Struggle by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries Volume III: The Fury by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries Volume IV: Dark Reunion by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries: The Return Volume I: Nightfall by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries: The Return Volume II: Shadow Souls by L.J. Smith

The Vampire Diaries is,,,not great, if i'm being honest. the series if rife with various forms of bigotry and feels more exemplary of heterosexual (mis)readings of vampirism than Meyer's Twilight Saga. i'm not sure that i will be considering using the books as reference for contemporary vampire Gothic literature.

my roadmap for this year is to get my thesis drafted, focusing primarily on outlining my Queer and Gothic design principles (from now on, i'm going to condense that into one title –– Queer Gothic). after that (which should be done before 2022 begins) i will use my Queer Gothic principles to guide the design and creation of a queer vampire visual novel. the rest of my thesis will be a post mortem of both the game and my thesis as well as, potentially, outlining how i could change the design principles in future iterations.

thesising – vampire blood tracker app part one

it should come as no surprise that i am thinking about making a vampire game for my thesis. right now, i'm working on designing some screens for an app that would exist in the fiction of the game world. (or, my other idea, the app is a real all that you experience the narrative through the "conversations" and interactions.)

i've been posting occasional updates on my original tracker apps, but i really started doing design and iteration this past weekend. the result is the eight screens below. i've also included the thumb reach map (which i used to place elements within – or out of – reach) and a style guide (for documenting the colors, font choices, and shape/icon language of the app in order to give the screens a cohesive feel).

this app is supposed to feel like a blend of UberEats, a period tracker, Tinder, a calorie tracker, and a standard messaging app. i wanted each screen to have one purpose in order to make the app easy to read and navigate. the potential users of this app are vampires that are possibly hundreds of years old and an accessible design is essential (both to my own work and to this piece's fiction).

there are a few errors that i made in these. the Blood Tracker screen says 79% and 435 mL but it should say 71% and 391 mL. the dial also needs to be rotated so that it fills up clockwise from the 12 o' clock position. the Find Familiar screen is a map of Santa Cruz and the river is positioned above the streets (though there is a question as to whether or not vampires can cross moving water). additionally there is a small B-shaped lake at the top of the map that i filled with the wrong color. on the Messages screen, the keyboard letters need to be a little bit smaller so that they fit on the keys better. i believe that the top area on the Order Blood screen is slightly lower than the rest of the top areas.

this is still a work in progress but i wanted to post an update on my work since i've made a fair amount of progress and that's worth presenting!

now to explain a little bit about the world this app lives in. this app is for vampires and there is a companion app for humans offering blood or looking to be turned. vampires can communicate with other vampires and humans via instant messages, but this is not a social network where you post updates. its more akin to a food delivery app (which brings in some snark or humor, because this app parodies popular, omnipresent apps in out Pandemic Lives™). at the top of the home screen is the sunrise reminder for the vampire users and it would send alerts as sunrise gets closer.

i placed the most important functions (for the developer) within the Green area on my Thumb Reach Map and hid non-interactive features and also the Profile button (where one could change their subscription or cancel their account) in the Red areas and borders.

thesising - drafting a game design document

it's nearing the middle of winter quarter 2021. i mean it's almost the end of week 3. i guess that isn't too late into the quarter. i haven't done tons of work on my thesis. that's probably perfectly fine – next year is when a lot gets done. but i would like to start earlier. so tonight, i sat down and drafted the very first version of my thesis project's game design document. i don't know how useful this will be for a solo project, but it gives me a structured document where i can hash out the details of the game (and document it, save it, and upload it somewhere).

which is what i'm doing now.

so what is my idea? good question. i'm planning on making a game that is both visually and structurally Gothic and queer. i'm still fleshing out some design pillars in order to make sure those goals are at the forefront of my process. right now, i'm considering making a narrative game – probably a visual novel – where players explore a small university (yes, i am cashing in on the dark academia aesthetic. it's gay. and it can be Gothic), meet students and professors, and eventually get turned into a monster (of their choice, i think). there will be some "minigames", mostly involving some apps that i am designing like my Blood Tracker app and my Moon Cycle app.

the game design document i've drafted up tonight is merely the foundation for my documentation, and i will include updated pdfs in future posts.

vampire blood tracker app mockup

werewolf moon cycle app mockup

wrapping up my first quarter

Fall of 2020 was rough. Like, really fucking rough. And not just in the sense of "there's a combination pandemic-fascist coup-economic crisis-class war". I mean, yes in that sense, but also every month of Fall Quarter brought new tragedy to my life. In October my long-term relationship ended. In November, my brother died. December didn't have death or destruction in my personal life, but I did have to make it through the holidays without him and it would be an understatement to say it fucking sucked.

But I survived.

I haven't started making anything for my thesis project (I'm still researching), but I did make some small games! Most of these are private games with personal information, but I explored home, ritual, and familiarity versus unfamiliarity. I don't think I want to make more games about those topics right now, but that's because I am Hyperfixating™ on gay vampires and that's kind of my whole brand at the moment. (I even made social media headers about this.)

I did finish a few close readings. I annotated The Queer Games Avant-Garde, Gaming at the Edge, and Interview with the Vampire. I also read The Vampire Lestat and have found a new (academic) book that I'll be reading in between my classwork this quarter called Queer Gothic Culture.

Since I'm making more games that I think I can share, I'll write up separate posts about them and document my progress. For now though, I am content to do my readings and classwork.

here is a link to my end of quarter presentation

starting my mfa

okay, so technically i started the DANM program five weeks ago, but there's been a lot of adjustment so I'm cutting myself some slack. i didn’t know i was going to apply to the MFA program until january of this year and the combination pandemic-class war has been really intense and scary and draining, so i didn’t get to do all the research that i was looking forward to doing this summer. my plan was to read texts about queerness, gender, and identity in game studies and game design. when i applied, i mentioned an interest in queerness, accessibility, and challenging systems and structures of power. my focus has since changed slightly. namely, i want to shift my research away from accessibility (not abandon it, it is imperative that my work is accessible) and towards queerness and identity specifically in the context of Gothic literature and game design that promotes Gothic themes of villainy, monstrousness and identity, absolute morality, queerness, and (religious) abuse and trauma. i'm considering focusing on vampires (and werewolves) and the current format i'm imagining is some sort of rpg/visual novel-adjacent design to allow a narrative element shape the player experience. i’m currently compiling notes and quotes from my self-assigned readings and plan on creating both queer and Gothic design pillars for my thesis work.

this is the introduction presentation i gave to my peers.